In the fall of 2018, if you were to guess who was advocating for Python at RStudio, you may have guessed it was me. I had given a webinar on using R and Python together with the brilliant reticulate package. I had written about Python powered shiny applications. As a technologist I was excited. It was fun to glue the two languages together, the details of the C++ implementation were intriguing, and the results, in true JJ fashion, were magical.

But all that magic aside, as a product manager, I was surprised when both JJ and Tareef proposed adding support for Python across RStudio Team. My role at RStudio was to shepherd the professional products (RStudio Team) that help fund RStudio’s open source work. Most commonly, this role meant balancing the grand visions of JJ and Tareef with the immediate requests of our customers, engineers, and support teams. In this case, the grand vision came first. Tareef and JJ were concerned that data science teams wouldn’t purchase tools just for R. They wanted to ensure RStudio Team could stand against other multi-lingual platforms. I was afraid we would loose our competitive advantage. The strategy for RStudio’s professional products is to build incredible experiences for users, based on the open source foundations we own and control. To me, the idea of adding Python into the fabric of RStudio Team was akin to Chick-fil-a adding hamburgers to their menu. Would the brand crumble? Would the tools miss the mark? Would users revolt?

We began by talking to customers and trying to identify a first step. Jupyter Notebooks were the lingua franca, despite a user experience that, in my view, was pretty lack luster1. We soon found a pretty interesting anecdotal trend. Contrary to the intuition I had gathered from a weak exposure to Python twitter, it turned out Python data scientists faced a similar challenge to R users: while they were writing code they were not software engineers. This meant that, just like R users, they struggled with deployment and sharing their work. It turned out Python data scientists found docker just as intimidating as R users2. Even larger organizations running JupyterHub weren’t thrilled with the experience of sending executives links to the clunky Jupyter interface.

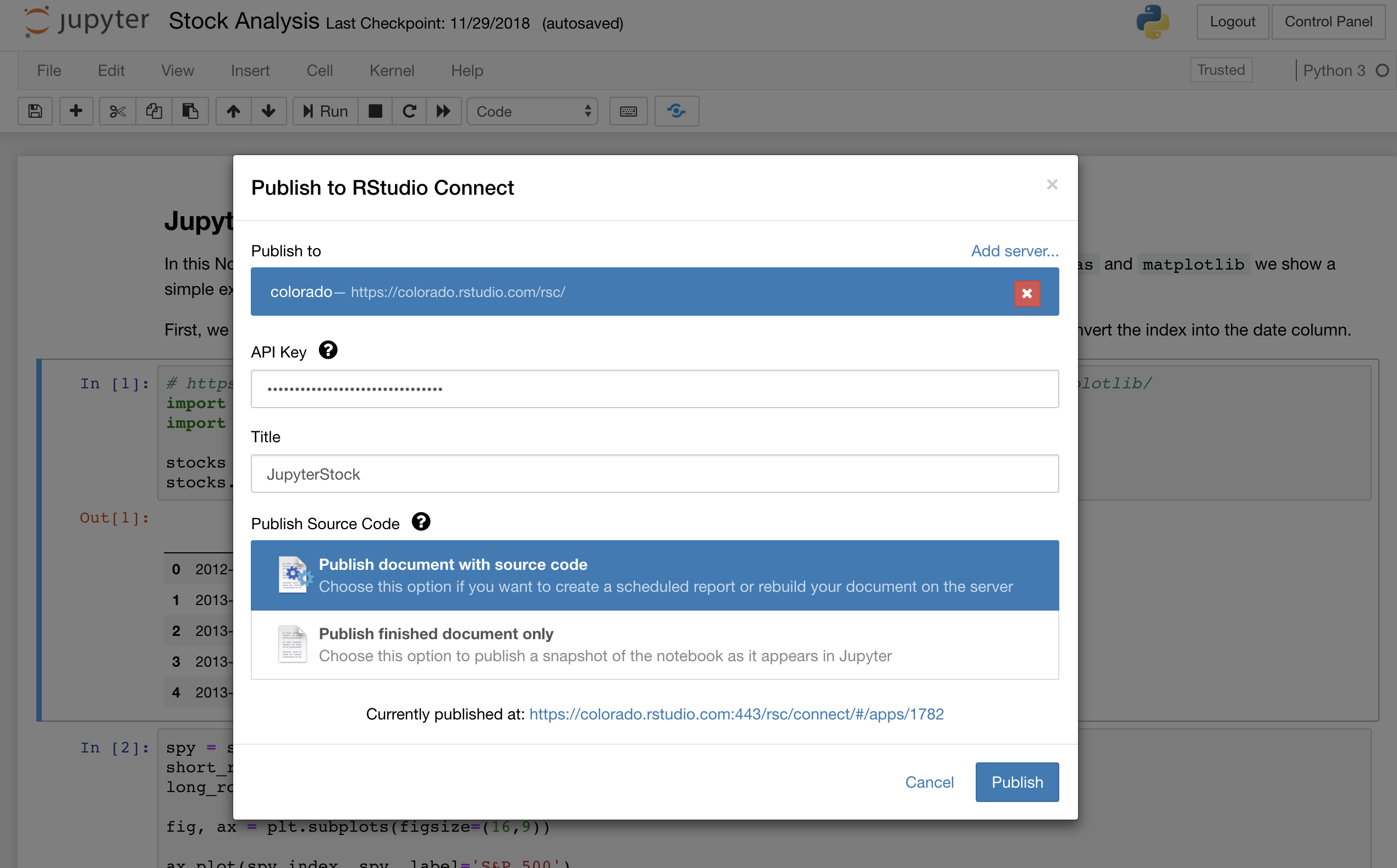

We hatched a plan to add support for Jupyter Notebooks to RStudio Connect, our platform for sharing data products. The execution model would be similar to R Markdown, Notebooks could be re-rendered on a schedule, but the default experience for users would be a pre-rendered HTML page without an active kernel. Vice president proof. We also wanted to make publishing just as easy as it was in R, enabling a single button push to move a notebook form local development to production3. This desire meant quite a bit of plumbing, figuring out how to capture a user’s python dependencies, and how to recreate the right environment on the server (for scheduled re-runs).

The reception to the change in Connect was slow but positive. Users didn’t revolt. The brand didn’t crumble. Pretty soon we were logging and tracking requests for other types of content. Data science teams familiar with plumber APIs and Shiny saw opportunities for their Python counterparts to deploy something interactive without talking to IT.

But even given this success, I was still skeptical. We wanted to add support for Jupyter to RStudio Server Pro, turning the professional IDE into an IDE workbench. I hated the idea. There were also plans to add PyPI mirroring to RStudio Package Manager, a move that would be expensive and face stiff competition.

Fast forward two years and the bets have made progress, the results are promising but pending. We haven’t lost any business because we’re R-only. (Though who knows what the counter factual would entail). The analysts eat up marketing’s “love story”. Our data from customers suggest that Jupyter in both RStudio Server Pro and Connect is being used, and adoption of other Python content types will likely follow as customers upgrade versions.

But as a product manager I still wonder if we’ll be able to build a truly differentiated user experience without going deeper into the Python open source ecosystem. Typically product management is responsible for ensuring the right thing is built for the right reasons. At RStudio, however, most of the magic has come from open source engineers sitting in the trenches with users. We’ll have to build that muscle for Python. I see promise as the RStudio IDE adds richer Python support and I wonder if the improvements to R Markdown editing will be just as game changing to Python Markdown editing.

So what is the lesson here? I think the morale to this rambling story is simple: product management is hard. At one time you have to sell a vision to engineers and in-progress products to customers, all while being in the best position of anyone to have doubts. You see the opportunity cost of every bet - why take this risky big move when there are small sure bets? You see the cracks in the data, the counter arguments to decisions. My advice if you find yourself in these situations is to stretch the time horizon. RStudio’s goal is to build a durable product, measured in decades not VC rounds. When you stretch the time horizon you allow yourself to watch bets play out, to adjust as data comes in, and to evolve as the market adjusts.

In the grand scheme, I am also proud of a change in the market that we’ve witnessed. Two years ago the R vs Python debate raged. Now, in a world where mutually exclusive polarization is the norm, I see more teams talk about using R and Python. I see more job descriptions open to either. I don’t know if our “love story” and product investment moved the needle. I hope it did, and I hope it continues to. Regardless of the bets we make in our commercial products, I hope to see data scientists encouraged to use tools they love in any language.

When you are used to using R Markdown in a full fledged IDE, using a tool where you have to insert a chunk to write markdown feels very clunky.↩︎

I think many make a mistake by not segmenting Python into Python engineers and Python data scientists.↩︎

At some point on this blog I’ll discuss why we decided to use

pip freezefor this support instead of conda.↩︎